At the Border: About Migrants, Challenges and Dreams

They are fleeing economic misery, natural disasters, criminal gangs, police brutality, political persecution

Beyond nationality, race, language, the common denominator of men and women and children who from remote regions arrive at the US-Mexico border with a bundle on their shoulders, is hope. The hope of a better life.

They are fleeing economic misery, natural disasters, criminal gangs, police brutality, political persecution.

Sometimes walking through desolate deserts; others, crossing vast territories in cars, trains, buses. They arrive with their few belongings at a border where the first thing they see, in that geography of hope and misery, is the imposing wall erected on that imaginary line that divides two universes.

Walls can serve as barriers to protect us from danger, but they can also be used to divide us. In his poem La Muralla, the Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén criticizes the walls built by those who poison with their intolerance.

“To the heart of the friend, / open the wall; / to poison and to the dagger, / close the wall; / to the myrtle and the mint, / open the wall; / to the serpent’s tooth, / close the wall; / to the nightingale in the flower, / open the wall…”

The wall is impenetrable. Some reach out, touch it, run their fingers along the metal, acknowledging it, confirming the impassable nature of the beast.

A Shelter

The concentration of thousands of migrants from Latin America, the Caribbean and from other corners of the planet, who survive in more than precarious conditions on the Mexican side, has attracted governmental and non-governmental organizations with a humanitarian mission.

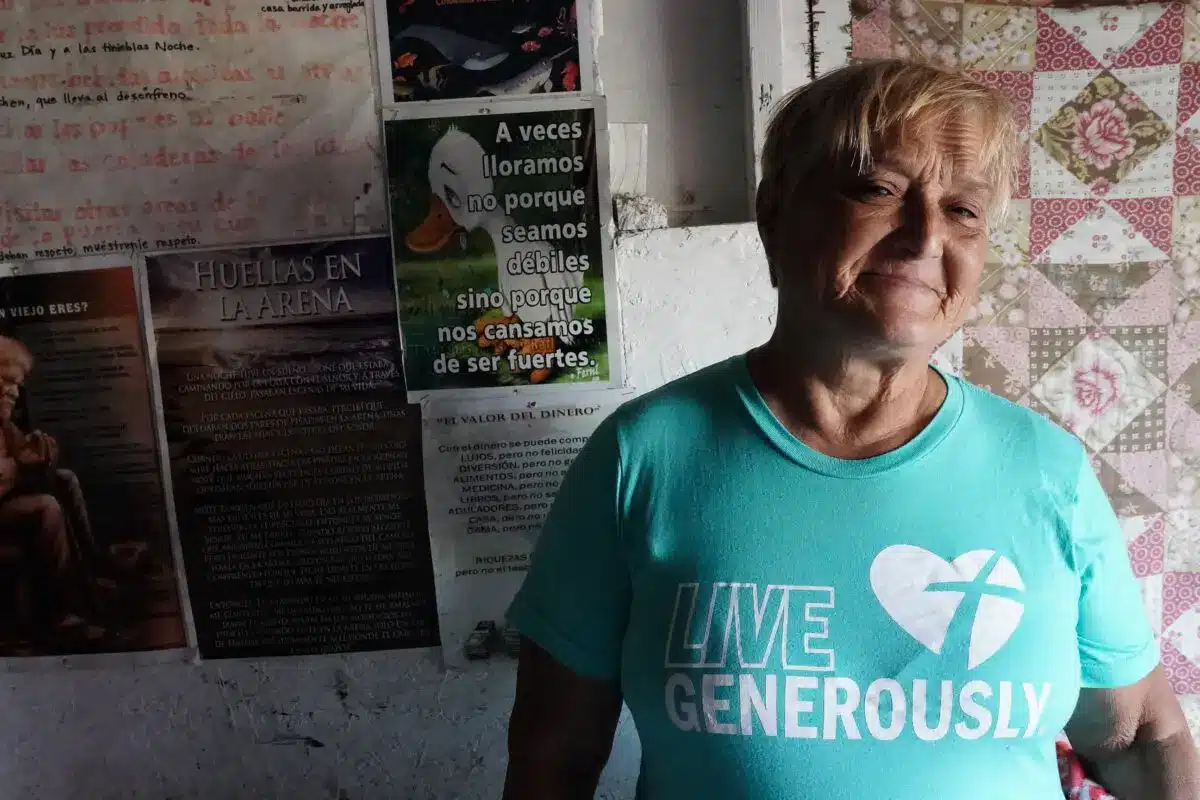

Esperanza Lozano, the coordinator of Templo Embajadores de Jesús Shelter in Playas de Tijuana, strives to aid those who come to her for help during their uncertain and seemingly endless wait. They are unable to exercise their right to request asylum due to the legal impasse in Washington, DC, and Esperanza does her best to support them in the meantime.

Migrants

They come from numerous states of Mexico; from Honduras and Guatemala; there are migrants from Venezuela, Haiti, Ecuador, Cuba, and even Russia.

Each one has a story, a past, and now they want to start a new chapter. But first they have to cross. They are close, but they are not close. They are told about confusing regulations like Title 42, TPS, about the asylum process, and that there is no alternative but to wait. And then the shelter opens its doors. And beyond the shelter, beyond the wall, their dream.

That is the dream of Reyna, 37, originally from Honduras, with her 7 and 2 daughters who wait patiently at the shelter. Her girl looks at the camera sweetly. The mother looks tired. A face of resignation, acceptance. Perhaps already aware of the impossible task that she confronts. And the smallest, absent, in another world, is distracted by what looks like a cell phone that projects a hopeful light.

It is the dream of so many others, thousands, tens of thousands… of Magali and Angelina.

Broken Dream

Some are successful and arrive, cross over, enter the womb of the American nation that over the centuries has been nourished by new blood. Blood that rejuvenates it, makes it grow, oils the machines of its industries, softens the land of its fields. But sometimes dreams don’t come true and, despite so many projects and planning, the glass castles fall to pieces.

Laws limit possibilities, the impenetrable wall, the desert that disorients, the endless ocean. And on that November 9, 2022, members of the border patrol recognize the corpse of a Russian immigrant who tried to reach the dream, perhaps desperately, by swimming the waters of the Pacific.

Who is he? What´s his ame? Why did he come? Was he escaping from war, misery? Did he have sons, daughters? Mother, grandfather, friends? Is there someone who is thinking about him? Will they ever know his fate?

– – –

The content of this article includes photographs of Francisco Lozano who was entrusted by Hispanic LA with a visit to the US-Mexico border on November 9, 2022.

This article was supported in whole or in part by funds provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library and the Latino Media Collaborative.